The Airlie Beach community is pretty tough. I discovered this when I did some interview research after Airlie Beach was hit in 2010 by Cyclone Ului, which was a Category 3 cyclone when it made landfall.

So what will the people in this community be doing right now?

Information gathering will be a focus, between long periods of cleaning up.

Based on my interviews, in the days after the cyclone most will be trying to get a sense of what the destruction means for them in terms of home and work. This means checking out their properties and checking on neighbours.

Some might even drive to work to see if it is still standing. All very rational behaviour.

Once they have this sorted out, they will be looking out for friends or getting together with the community groups they belong to, and setting up sausage sizzles for the stranded backpackers or clearing up for older neighbours.

By Day 2, they will be working with other people to clear their homes and neighbourhoods.

The questions I asked in 2010 were about their experiences leading up to, during and after the storm, and how they got information about what was happening. People’s approach to the cyclone was calm, educated and practical.

Most heard early (about six days out) and used their normal weather website to track the path of the storm. They talked to other people about it, but the experienced people made their decisions based on information coming from BOM and other well-known websites.

Residents fairly new to the area and who hadn’t experienced a cyclone consulted friends, relatives and neighbours who did have experience.

Everyone used the information to trigger their preparation – some relying on experience to guide the process, some referring to council and agency preparation materials they received at the start of cyclone season or had in their Sensis phone book.

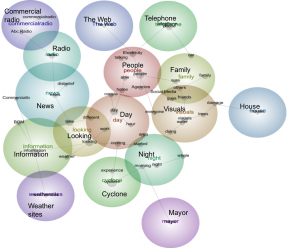

This diagram shows what their activity looked like and where its focus was – each of the bigger circles represents more mentions of concepts within these themes, and more connections to other concepts. To generate this map, I fed all the interview transcripts from Airlie Beach into concept mapping software to see what the main themes were and how they were connected with others.

You can see the biggest  circles (which represent the most interconnected activities) were news, information and visuals. Other people were a feature too – you can see this by the more intense colour on this circle and its close relationship to family.

circles (which represent the most interconnected activities) were news, information and visuals. Other people were a feature too – you can see this by the more intense colour on this circle and its close relationship to family.

News was the biggest – which seems like a no-brainer. Everyone wants to know what is going on, the extent of the damage and what it means for them. The big component of this need for news is making sense of what the situation means for each family or individual – can they go to work or school when this is all over, will they still have an income? Sense-making is a big driver for the information-seeking process in disaster literature, and much of that will happen the day after the cyclone – Wednesday, for people in Airlie Beach. It will probably go on for weeks for some people.

Information is very tightly linked with news in this sense-making activity. It has been separated from news in this computer-generated analysis because the linkages are not only with news, but other sources of information such as agencies and – most of all – other people. You can see it is also very close to the concept ‘looking’ – in fact, news, information and looking are a cluster with connections to other key sources, radio and weather websites.

People and family are separate but joined concepts, and these are among the most important sources of information for anyone involved in any disaster. So today, people in Airlie Beach will be listening to their battery-operated radios as other people call in to report damage. This important information will enable residents to get a sense of what has happened to their community. They will have contacted friends and family. Those family and friends outside the district will have added more pieces to the jigsaw showing the big picture of what just happened. Other people will remain a key source of information throughout the recovery process. It will become most distressing for residents if they lose contact with family and friends because landline, internet and mobile phone connections are down.

What this diagram shows is that agencies will have to be very good at communicating across all sources of information, particularly harnessing ‘other people’ to help spread the word about what has happened, safety issues, what is going to happen and the recovery process.

Perhaps one of the biggest takeaways from my interviews at Airlie Beach after that comparatively minor cyclone was its effect on the tourism industry. Tourist perceptions that the town had been destroyed persisted for months afterward, even though operators had cleaned up and were back in business within the week. This will be the case for the entire Whitsunday Coast.

Image by freeimageslive.co.uk – lion_down

Dr Barbara Ryan researches disaster behaviour and teaches in the Graduate Certificate of Business (Emergency and Disaster Communication) (which starts July this year) at the University of Southern Queensland. She used the content analysis software, Leximancer, for this project.

by four months past its usual end, Victoria and NSW working fire business as usual and cyclone watchers waiting for the big one, which could still happen in the next few weeks.

by four months past its usual end, Victoria and NSW working fire business as usual and cyclone watchers waiting for the big one, which could still happen in the next few weeks. the southern hemisphere, emergency managers will be thinking about a big one that might lead to evacuations. And it appears that local information is the key to informed evacuation decisions.

the southern hemisphere, emergency managers will be thinking about a big one that might lead to evacuations. And it appears that local information is the key to informed evacuation decisions.